I've been having a lot of fun working on Hydro at AWS this fall. But over the winter break I stepped away from coding and had the space to think ... mostly about fundamentals of long-time obsessions around concurrency, coordination and correctness specs.

I don't have specific results to report here (yet :-)). Instead, I thought I'd share a conceptual contrast that’s been clarifying a lot of my recent thinking

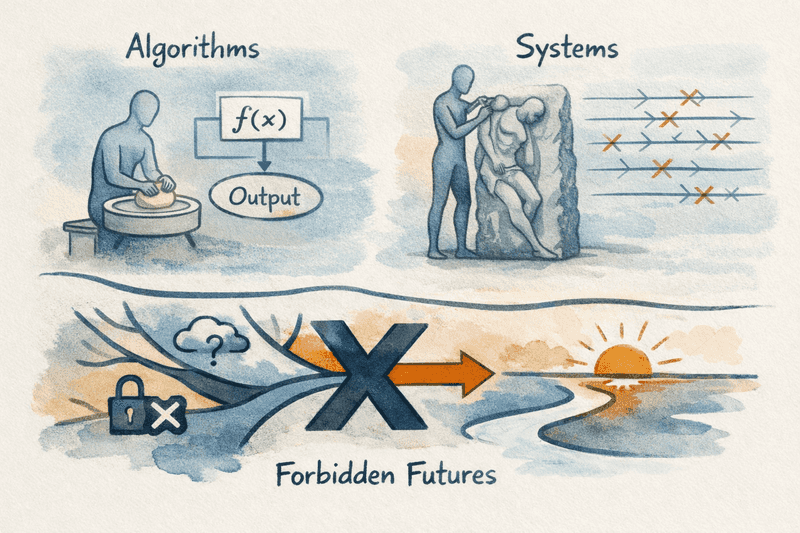

Algorithms compute functions.

Systems make promises about preventing futures.

That sounds negative, but it's pretty on point. Most systems guarantees are prohibitions: states that may never occur, histories that must not be observed, interleavings that are not allowed, etc. And in many systems, the promising is an ongoing process: the set of promises evolves continually based on the system's observable behavior in the outside world.

A system’s job is not to produce a single correct output and stop; it’s to keep running without ever crossing certain semantic lines.

This difference explains a lot of friction we see when we move ideas back and forth between algorithms and systems.

What Algorithms Do

When we write an algorithm, we have a pretty clear contract:

- You give me an input (possibly complex, possibly huge).

- I produce an output.

- Correctness means the output corresponds to the function we set out to compute.

We might worry about efficiency, approximation, or even randomness — but fundamentally we’re evaluating a function. The algorithm is allowed to wait to see all of its input; it doesn’t have to make irreversible choices until it’s ready.

There’s a clarity to this world. It’s like working at a potter's wheel with the clay in front of you.

That’s a comfortable world. Meaning is fixed by the problem statement; the algorithm’s job is to compute it.

What Systems Do

Systems are "online" -- they exist in time. They interact with an environment (clients, networks, the physical world). They necessarily observe partial information. They do not get to pause the world indefinitely while they think. What “correctness” means here isn’t producing the right answer once — it’s never violating your invariants, ever.

Promises are a qualitatively different thing than answers: they’re commitments about what futures remain possible. I.e. systems prevent things from happening. Systems rule out futures.

In many cases (transaction commit, leader election, scheduling one process before another), once a system rules out a future, that exclusion is permanent. The system has committed.

To take an example from my home field of databases, if we have two conflicting concurrent transactions , the database system must make a hard exclusionary promise: if it lets commit, it promises that 's writes will never be visible to other transactions. The system "picks a world of histories" that excludes histories where 's writes are visible.

Why “Acting Before Understanding” Matters

This is where things get interesting.

Algorithms are allowed to wait until everything is well-defined. Systems often aren’t.

A database must commit or abort a transaction before it knows what other concurrent transactions may want to do next. A distributed service must respond before it knows which messages are delayed. An online learning system must deploy a model before it has seen tomorrow’s data.

In each case, the system must act before the world is fully known. That action whittles away possibilities until only an acceptable outcome is revealed. The meaning of the system is defined by removing the negative space, being left with only observable behavior that satisfies the invariants.

Systems construct meaning like sculptors make art:

by chiseling away the negative space in a world of possibilities.

This is the common structure behind a lot of familiar problems:

- coordination

- consistency levels

- isolation anomalies

- optimistic execution

- speculative and asynchronous learning

They look different on the surface. Underneath, they’re all about deciding which futures to forbid, and when.

I plan to keep chipping away at this idea in future posts.