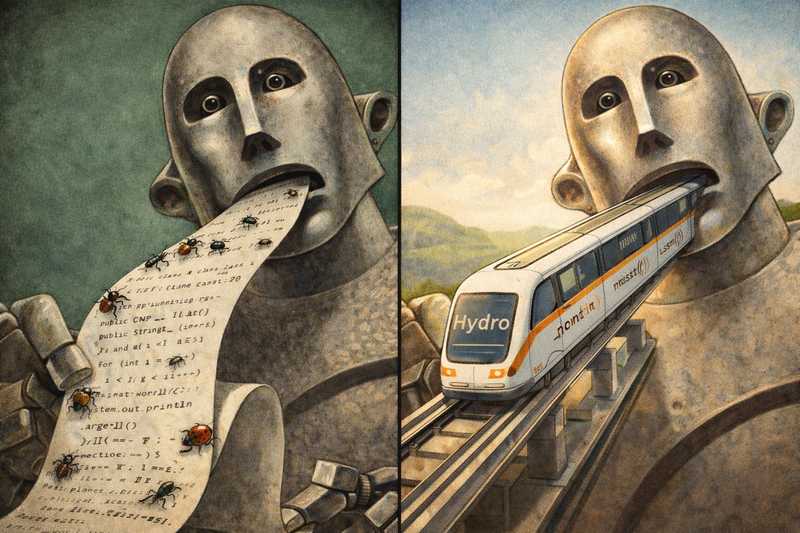

AI is about to write most of the code in the world.

Most of the code in the world participates in a distributed system.

And distributed code is where our worst bugs live.

That leads to a simple thesis: AI should aim at languages where many distributed bugs can’t be expressed at all.

The collision course sketched above is the story of the next decade of systems engineering. We can celebrate the productivity—and we should—but we also need to ask a harder question: what language constructs do we want AI to aim at? If the target is ordinary imperative code, we’ll get ordinary distributed bugs, only faster. If the target is a framework that makes many of those bugs impossible to express, we get something very different.

That’s the argument of this post: the right target for AI is a framework where distributed systems bugs are largely impossible to express. Hydro is one such framework for distributed programs. The alternative—plain code plus increasingly heroic testing—is reasonable, but it carries structural downsides that matter more as AI scales.

The ground we’re standing on

Today, every “simple” app is a distributed system: a phone talking to a cloud service, which talks to other services, queues, and databases. Distribution isn’t an advanced topic anymore; it’s the floor.

At the same time, LLMs are getting good at turning English intent into working programs. That’s intoxicating. You describe what you want, the machine fills in the ceremony, and a service appears.

But distributed bugs don’t respect ceremony. They show up after retries, batching, and unlucky orderings nobody pictured when the code was written. They can sleep in stored state for months and then wake up on a Tuesday afternoon. LLMs are excellent at happy paths; the corners of distributed behavior are not happy places.

We’re about to try and automate the hardest part of our craft.

Testing is necessary — and bounded

The natural response is: test harder. And we’ve never had better tools. Bounded model checkers like TLA+, Alloy, Jepsen, and Antithesis can explore real systems brutally and systematically. That work is a triumph of our field.

And yet, while bounded model checking sounds like proof, it actually isn’t; it’s just finite exploration. These tools are disciplined fuzzers: they examine a large space, yet still only a slice of what production will see—endless request diversity, long-lived state, retries, flaky networks, and occasionally adversaries. The part you don’t explore dwarfs the part you do.

Model checkers don’t guarantee correctness.

They guarantee you didn’t find a bug in the executions you looked at.

That’s not a criticism; it’s the math of state explosion. In the cloud, your service runs for years under traffic patterns no bounded test suite can enumerate. Reality is a far more aggressive fuzzer than our fuzzers.

Which means the real question isn’t how much we test, but what surface we test against.

Bounded testing explains why we miss executions; the deeper problem is that even the executions we do see rarely reveal what went wrong.

The failure mode tests can’t diagnose

Even infinite search wouldn’t fix the outages that hurt most: the ones that arise from mismatched and unstated assumptions between components.

One service assumes ordered delivery; another produces unordered batches. Ninety-nine percent of the time the combination works. In the one percent case, a rare permutation violates an unstated contract and the system’s brain is split for the rest of time.

A checker can show the trace where that happened.

It can’t tell you what assumptions were made incorrectly, or what the overall intent might have been.

The problem isn’t lack of exploration. It’s that distributed contracts have no obvious home. The English prompts and specs talk about high-level goals. The generated imperative code talks about procedures. The contracts between components—ordering, retries, idempotence, and so on—float in the gap between them. For an LLM, that gap is invisible, so it fills it with guesses.

Target matters

If ordinary code leaves contracts implicit, some framework has to constrain the code so those contracts become explicit and checkable. This is where the choice of frameworks becomes decisive. Hydro takes the stance that distributed behavior should be deterministic by default—e.g., unordered collections cannot silently feed order-sensitive code—and that deviations from determinism should be explicit and signposted.

In Hydro:

- choices about ordering and delivery are explicit in interfaces,

- compositions that violate those choices are compile-time type errors,

- the few places where behavior can truly diverge are marked with a keyword:

nondet!.

The point isn’t to outlaw uncertainty. It’s to give it a narrow scope and signpost.

Instead of:

Write a service that processes events and retries failures.

You ask:

Write a Hydro service with unordered input and at-most-once output,

nonondet!blocks.

Any use of order-dependent logic then becomes a compile-time error.

The difference is not who writes the code, but what the code is allowed to say. The agent still writes code, but the tricky distributed assumptions become machine-checked facts rather than folklore. Many races and other heisenbugs simply cannot be expressed without crossing a bright line at compile time.

Tradeoffs, not perfection

That promise—eliminating whole classes of heisenbugs—is deliberately narrow. Hydro does not attempt to verify full application semantics. It won’t prove your business logic is right, your protocol matches a spec, or that a system meets liveness goals. What it targets instead are the failures that bounded model checkers spend most of their time hunting: accidental nondeterminism from hidden ordering, retries, and delivery assumptions. By making those choices explicit, many of the traces that checkers labor to discover simply cannot arise.

This tradeoff is deliberate. We can’t yet automatically reason about every aspect of open-ended cloud systems, but we can remove the layer of unpredictability that turns small design mistakes into sprawling search problems. The analogy is Rust: memory safety doesn’t guarantee a correct program, but it eliminates an entire class of failures so we can reason at a higher level. Hydro aims for that kind of foundation for distributed behavior.

A separate, practical wrinkle: today, models are less fluent in Hydro than in plain Rust. That will improve with better training and tooling, but even now the constraint is useful—it pushes generation toward explicit contracts instead of silent assumptions. The goal isn’t AI that writes anything; it’s AI that writes distributed systems we can reason about.

Checking with a map

Testing doesn’t disappear in this world; it changes character. HydroSim—the checker for Hydro—only needs to explore around the nondet! code sites. Deterministic paths can be trusted rather than tested; the search budget goes to the real ambiguity.

In practice that means deeper exploration of actual risks in the same time, and far fewer ghost counterexamples from harmless plumbing. The conversation shifts from staring at traces to talking about the spec.

You stop asking, “Did we test enough?”

You start asking, “Did we understand the few places where the program can diverge?”

The target AI should aim at

AI will generate oceans of distributed code either way. The question is whether we point it at a coding framework where distributed bugs are easy to write, or at one where those bugs require an explicit escape hatch.

Traditional imperative code plus model checking is still a sensible baseline. It will remain indispensable for legacy systems. But as a destination for AI code generation, it’s a poor default. It asks us to debug our way out of problems the AI could have prevented by design, simply by picking a better target.

Better testing finds more traces; better languages make many traces unnecessary.

The real opportunity

Going live in the cloud will always provide a more comprehensive test than any checker can offer. The durable response is to change how we express distributed programs so that intent is visible long before the first counterexample appears.

Most future distributed code will be AI-generated. The practical choice isn’t whether we’ll test harder, but what target we’ll ask the AI to aim at. If we aim at ordinary imperative code, we commit to finding problems after they happen. If we aim at frameworks where distributed contracts are part of the language surface, many of those outages never get a chance to exist.

Hydro is one example of that kind of target: a setting where ordering and delivery are explicit, and the few genuinely uncertain steps are clearly marked. Targets like this don’t eliminate testing; they focus it on the right questions instead of chasing shadows.

Give AI a target that reflects distributed reality, and it can help us build systems that fail less often—and for better reasons.