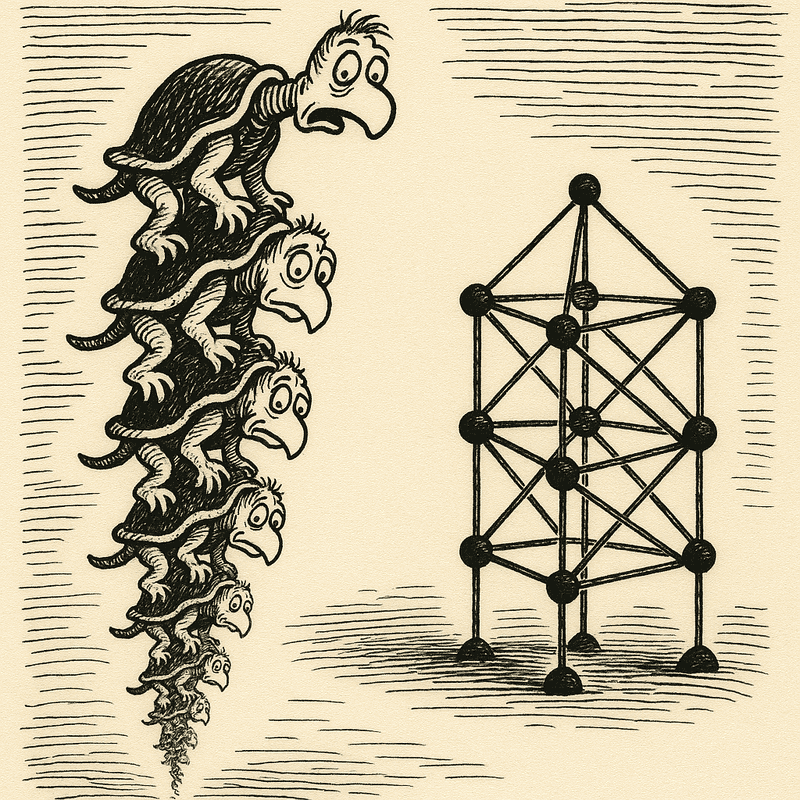

After a lecture on cosmology, William James was challenged by a skeptic:

"Your theories are incorrect. The Earth rests on a turtle,"

"And what holds up the turtle?" James asked.

"Another turtle," came the reply.

"And what holds that up?" pressed James.The skeptic was undeterred:

"You can't fool me, sir. It's turtles all the way down."— Anecdote attributed to William James (via J.R. Ross, 1967)

This is the 2nd post in a series of 4 posts I'm doing on CRDTs. Please see the intro post for context.

Modern distributed systems often seem to rest on an stack of turtles. For every guarantee we make, we seem to rely on a lower-layer assumption. Eventually we're left wondering: what is at the bottom?

CRDTs — Conflict-Free Replicated Data Types — are often advertised as a foundation we can finally trust. They promise convergence of state across machines without requiring perfect clocks, global operation ordering, or causal message delivery ... and they do it with math.

But many CRDTs sneak in assumptions that don't belong. That's not solid ground. It's not math. It's turtles.

In this post, we’ll show how to design CRDT internals properly:

-

✅ Always in terms of a semilattice structure.

-

✅ Always with clean algebraic reasoning, without hidden dependencies.

-

✅ With explicit causality lattices included whenever needed.

This will ensure we're always using careful reasoning.

Correct CRDTs are semilattices at bottom. And that's math you can count on.

🐢 A Principle for CRDTs: Semilattices All the Way Down

Every well-designed CRDT is a semilattice.

- ✅ A semilattice defines how information grows and

merges. - ✅ It provides convergence by construction, through clean algebra.

In case you've read about a split between so-called "state-based" vs "op-based" CRDTs, you can ignore that for now; it's a turtlish distraction I will fill in below. Here’s what actually matters:

A semilattice is:

- A set of states

- A

joinfunction that must satisfy commutativity, associativity, and idempotence. Thejoinfunction induces a partial order: .

When discussing CRDTs, people often use the term merge instead of join.

CRDTs sometimes add additional "update" operators:

updateupdatetakes an input value of type and uses it to directly mutate the local CRDT's state.

If all pairs of nodes eventually merge state in an associative, commutative and idempotent manner, then eventual convergence of a CRDT is guaranteed — no further assumptions required.

🔍 Common CRDT Mistake: Hiding Assumptions

Many CRDT descriptions assume causal message delivery, message uniqueness, or reliable clocks ... but fail to encode these in their semilattices.

🚫 That’s like putting turtles back under the CRDT again!

✔️ Design Rule:

All required assumptions must be internalized in the semilattice structure.

-

If your algorithm needs causality, encode it.

-

If it expires or compresses away state, model that algebraically too, and make sure it respects the rules of a semilattice.

-

You can always optimize later (see below) ... but the math must be sound on its own.

Case Study: Add/Remove Sets

Let's walk through a concrete example. A 2-Phase (2P) Set is a simple CRDT that tracks a pair of set-based lattices (adds, removes) where merge is set-union for each:

- adds:

{(id, element)} - removes:

{(id, timestamp)}(sometimes referred to as tombstones)

The 2P-Set is a free product of these two set lattices, which is to say that the 2P-Set merge operator is simply the independent merge of 2 adds sets, and 2 removes sets:

Updates are simple: add an item by inserting into adds, delete an item by placing its id and time of deletion into removes. All good.

Until... you try to expire tombstoned data to save space.

Observed-Remove (OR) Sets

The OR-Set CRDT extends 2P-Sets to allow tombstones to be expired, but ... it's tricky! Let's walk through it.

A naive scheme for expiring tombstones might work as follows: look at a local wall-clock, and expire ids from adds and removes whose tombstone timestamps are "older" than a threshold. Turns out that this would be bad! Making this decision based on local time can cause non-convergent behavior.

This is not at all obvious (in fact, ChatGPT happily provided incorrect proofs in both directions!), so I constructed a proof by example. The basic idea is this: even after all updates have been issued, nodes can pass an item back and forth as a "hot potato" indefinitely, and never converge despite communicating infinitely often!

Click to see a non-convergent OR-Set cycle infinitely.

This diagram shows an oscillating state change cycle -- a single item in an OR-set that uses naive local expiry and never converges, just keeps rotating from state to state forever. Each 'pie' represents a global state of the item, across each of three nodes, A, B and C. In each state, each of the machines either has the item only in the adds set (+), in the adds and removes sets (—) or in neither (?). Edges are labeled with state transitions: xp@A means that the item expired at node A; B <- A means that node B received a copy of the item from node A.

Click on the image to zoom if needed.

🧯 Fix: Explicit Causality

This brings us back to the main point of this post: we need to explicitly include information in our OR-set semilattice ... in this case, to support convergent expiry of state. Specifically we can use a nested semilattice to track a causal context—e.g. a version vector—and use that to determine when it's safe to expire items:

- ✅ Expire a tombstone only after every node is guaranteed to know about it.

Note that this constraint breaks the cycle in the diagram of non-convergence above! It forbids the edges S2 -> S3, S5 -> S6 and S8 -> S0: each of those edges represents a tombstone being expired when at least one node is in a green + state and doesn't believe the tombstone exists!

We enforce the constraint by making the OR-Set semilattice a lexical product semilattice:

(causalContext, (adds, removes))Unlike our previous free product, the merge operator for the lexical product only looks at its second field (adds, removes) when breaking ties on the first field causalContext:

Note that the causalContext is itself another semilattice! It tracks which operations have been observed system-wide. This tracking can be stale, but it is always a conservative lower bound. We can safely expire data from our OR set if it is older than our causalContext.

There are different implementations for causalContext, including version vectors or causal graphs. We'll work with version vectors since they're the most common.

Click to learn about version vectors.

We begin by ensuring that each node maintains a local clock -- a counter that increments by 1 each time the node applies an operation or sends a message. (Note that a counter is also a semilattice, where the domain is the natural numbers 0, 1, 2, ..., and the merge function is max.)

A version vector is a map from nodeIds to values from a counter lattice: it records the highest clock value a node has heard of from each other node. This map is itself a composite semilattice! Specifically:

- The domain is a map from

nodeId(the key) to a value from the latticemax(the value) - The

mergefunction is simply key-wise application of the value latticemergefunction (i.e.,max). If a key is missing from one input tomerge, we simply take its value from the other input.

Notice what we did here: we formed a composite semilattice (causalContext, (adds, removes)) out of very simple semilattice building blocks.

The merge functions of these lattices effectively invoke the encapsulated sub-lattice merge functions recursively.

It really is lattices all the way down!

Using Version Vectors for Safe Expiration

To use our version vectors, we will make a few small changes to our OR-set design:

- Each node locally maintains an overall version vector containing the

mergeof all version vectors seen so far: this is typically called a vector clock. It represents a high-watermark of our local knowledge of global progress. - When an item is deleted, its tombstone timestamp is set to the local vector clock.

We can now do expiration safely: tombstones are only expired if their timestamp is lower in the partial order than the local vector clock: if so, we can be sure that every other node also knows about this tombstone, and will eventually expire it as well.

A Note on Op-Based CRDTS

As mentioned above, many CRDT fans like to talk about two "different" kinds of CRDTs: normal ("state-based") semilattice CRDTs, and something called "op-based" CRDTs. I'm here to tell you that correct op-based CRDTs are also semilattices; the distinction is not fundamental.

An "op-based" CRDT is just a particular class of semilattice. The state of an op-based CRDT represents a partially-ordered log of operations (opaque commands). The CRDT's job is to ensure that the partially-ordered log is consistent across nodes.

The partial order among ops can be captured by each site tagging every new op it generates with a causalContext value. This ensures (1) that recipients of ops from node will have them ordered in the same way as did, and (2) operations across nodes are causally ordered, via the causalContext.

Specifically, the state of an op-based CRDT can simply be a set of (causalContext, op) tuples, with simple set-union as the merge function. The causalContext is ignored by the lattice merge, but carried along to preserve a consistent partial order of the log. One typical causalContext implementation is to use vector clock timestamps, with each node incrementing its entry in the vector clock for every op and message.

That's really all there is to an "op-based" CRDT: it's a grow-only set of causally-stamped commands.

Typically, op-based CRDT designs assume that the log at each site is "played" (eagerly or lazily), by executing the ops in their causal partial order to materialize the local state. This is only required to support a "read" operation, and hence is effectively outside the scope of the CRDT math. Because causal order is only a partial order, different nodes could "play" some ops in different orders. As a result, op-based CRDT designs typically require the ops themselves to be mutually commutative.

If an op-based CRDT has quiesced and propagated to every node, and the ops themselves are mutually commutative, then every node can "play" the log in some total order that respects the partial order, and all nodes will end up with a convergent outcome.

To summarize: an op-based CRDT is still just a simple set semilattice! The only wrinkles are:

- The items in the op-based CRDT set are stamped with causalContext to enable causally-ordered replay

- For the ops to be meaningful at replay time, ops across sites should be commutative.

🪜 You Can Build on a Turtle — But Know What It Carries

Sometimes, a system's lower layers provide additional guarantees that allow us to skip some details and rely on a turtle below us.

Example: If your network guarantees causal delivery, you can safely drop explicit causal tracking in your CRDT.

But beware: your CRDT is now resting on that turtle. If the network is not in fact behaving like a causal semilattice, your convergence proofs go out the window!

📌 Takeaways

- ✅ Every CRDT must be a (correct) semilattice

- ✅ Order comparisons must respect the partial order induced by

merge. - ✅ Model all necessary assumptions inside the lattice.

- ✅ Build on trusted turtles only when you know exactly what they can carry safely.

When you do all that?

It's semilattices all the way down.

That's math you can build on.