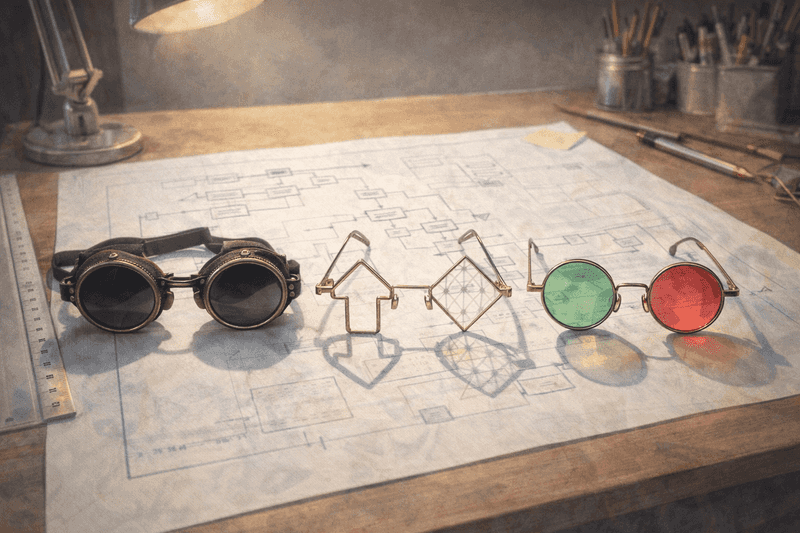

Three Sets of Specs (for Staying in Spec)

In the last post I talked about how systems formalisms are like sculpting with a chisel: we remove behaviors we don’t want, and what remains is correct. This subtractive view shows up as system invariants: concurrent actions shouldn’t conflict, replicas shouldn’t drift beyond reconciliation, and deadlocks should be impossible.

In this post we turn our attention to the work at hand: When is staying within spec easy, and when is it hard?.

This can be hard to reason about because the same underlying difficulty keeps reappearing in different guises. Sometimes it shows up as waiting. Sometimes as ordering. Sometimes as questions about what the system exposes to observers, and when.

In this post, I’ll look at these issues through three different pairs of "specs"—three ways engineers tend to first notice that staying within spec has become tricky:

- Waiting: when do we have to wait, and what are we waiting for?

- Ordering: how much order do we really need to impose?

- Commitment: what kinds of claims does the system expose to observers, and stick with?

We won’t do formal theory, and we won’t build protocols. The goal is to connect these different viewpoints and show how they fit together. Only at the end will we return to a practical question systems people care about: when do we actually need extra machinery—and when don’t we?

Lens 1: Waiting. “Come one vs. Come all”

We don’t like to wait in computing, but sometimes we have to in order to stay within spec. Waiting adds latency and can risk unavailability or deadlock. But at bottom, there are only two fundamental reasons we wait:

- Waiting for something to happen

- Waiting to know that nothing else will happen

Waiting for something

The first category is the familiar one. The clearest example is a data dependency.

If my job is to compute the function x + y, I have to wait until the values of x

and y are available (and perhaps the instruction for +, if we’re thinking at the chip level).

That’s easy to understand, and it’s easy to implement. The computation becomes ready exactly

when its inputs arrive.

But many cases of “waiting for something to happen” feel more complicated: they're not about passing data, they involve some notion of "control" messages. Nonetheless, many of these cases fall in this same category.

Consider message acknowledgment. I send you a message:

“msg m: 2 + 2 = 4.” Once I receive an "ack: m" from you, I know you’ve received it,

and I can proceed with that knowledge in hand—perhaps freeing the memory holding the

inputs and output. Until then, I’m waiting at your mercy. If you’re slow to respond,

I’m stuck. This can feel like a different kind of waiting—after all, I'm waiting for

“control” messages that are irrelevant to the "data" in my computation.

But this setting is not materially different from a function call. In a single-threaded program,

if my code calls a (local) function x + y, I can’t proceed as if x + y has completed

until the function returns. The return isn’t permission or agreement; it’s evidence that the work I

depend on has finished. The distributed acknowledgment plays the same role: it’s the signal

that the step I depend on has completed.

A function return doesn’t involve another machine, but the need to wait is already there. The distributed case doesn’t introduce a new kind of dependency—it just stretches an existing one across a network.

These ‘waiting for something’ cases are all instances of causal dependence on available evidence: once the needed event is observed, the waiting is over.

Waiting for nothing…or everyone

As a contrast, consider a different scenario: distributed termination detection.

Imagine I’ve paid for a global network of machines to work on a problem for me, and I want to know when that computation is finished. Intuitively, the computation is done when two conditions both hold: (i) no machine is currently taking steps on my behalf, and (ii) there are no messages in flight that could trigger further steps.

That sounds reasonable—but how do I establish those facts? Who’s to say that a message isn’t delayed somewhere in the network, ready to reignite the computation?

What I’m waiting for here is very different from the earlier examples. I’m not waiting for a particular event to arrive. I’m waiting for a guarantee that nothing else will happen. Formally, what I want to know is something like:

There exists no machine still working for me, and there exists no message in flight on my behalf.

That kind of claim doesn’t follow from causality. Causality tells me how events relate once they happen; it doesn’t tell me that no further events are possible.

Put differently, “nothing exists” is a universal claim (hello, DeMorgan!). To conclude that no machine is still working, I need confirmation from every machine. Waiting for nothing quietly turns into waiting to hear from everyone.

That reframing explains why this kind of waiting feels so different. In the earlier cases, progress was triggered by arrival. Here, progress depends on establishing a global absence. And absences don’t announce themselves.

This also exposes two immediate complications. First, I need to know who counts as “everyone.” If machines can join dynamically, or if the set of participants isn’t fixed, the target keeps moving. Second, even if I do know the full roster, what happens if one machine is slow, unreachable, or has failed? Am I allowed to proceed without hearing from it? On what basis?

These questions simply don’t arise when waiting for something to happen. Once an input arrives, the dependency is satisfied and computation can move forward locally. Waiting for non-arrival, by contrast, asks the system to make a claim about the future: that no further relevant events will occur.

This distinction—between waiting for arrival and waiting for guaranteed absence—is well known in distributed systems. It shows up in classic work on termination detection, and more abstractly in results like CALM, which formalize reasoning from positive evidence versus reasoning from absence. One kind of waiting is driven by evidence. The other is driven by exhaustion.

And that’s the tension to keep in mind as we move on. Waiting for something lets the system react. Waiting for nothing forces the system to make a claim about the future. Ordering turns out to do the same thing.

Lens 2: Order — partial orders and the cost of total order

Ordering problems often feel different from waiting problems, but they create pressure in a similar way.

Causal events naturally form a partial order: a DAG of events with “happens-before” edges. Many events are independent—they race, overlap, and have no inherent order between them. A partial order captures exactly what must be ordered, and no more.

But sometimes a system asks for more than a partial order. Sometimes it wants a total order: every event must be placed in a single sequence.

This comes up in very familiar places. Linearizability asks us to explain a concurrent execution as if operations happened one at a time. Serializability asks us to pretend that transactions ran sequentially. In both cases, the goal is to emulate a single-threaded program.

At first glance, this may not seem like a big step. After all, many total orders are consistent with a given partial order. Why not just pick one?

The answer is that a total order asserts strictly more than a partial one. It doesn’t merely say “event a happened before event b.” It also says that nothing else can come between a and b.

That second clause is a claim about unseen events. Here, “unseen” includes future events, and events that are delayed in reaching you.

A partial order can grow naturally as events occur. If two events are independent, their relative order can remain unspecified, possibly forever.

A total order removes that freedom. It forces a decision about the order of racing events—even when there is no causal reason to decide, and even when not all relevant events have yet occurred.

Once such a decision is made, it cannot be taken back without revising the history being asserted.

This is why systems that promise linearizability or serializability end up doing so much extra work. The cost isn’t in maintaining order where causality already demands it. The cost is in committing early, before the system has seen enough to know which total orders will remain compatible with future events.

That’s the tension to keep in mind. Partial orders let the system defer decisions. Total order forces it to decide—and to live with the consequences.

Lens 3: What the system is willing to expose

So far we’ve talked about waiting and ordering as properties of how a system executes. The final lens shifts perspective: from execution to observation.

In a distributed system, there is no single place where events are observed or understood. There are many replicas, each learning about the world at different times and in different orders. Any statement the system exposes to the outside world has to survive that fact.

In the easy cases, this works out well.

Statements like “this message arrived,” or “event a happened before event b,” are reports of observed evidence. They may be learned at different times by different replicas, but they do not conflict. Later information can add detail or context, but it will not make the statement false.

Because of this, replicas can safely expose such facts independently. Observers may see partial information, but what they see will only be extended, never retracted. The system’s public story grows by accumulating evidence.

The hard cases arise when the system exposes stronger claims.

“Nothing else will happen.” “This result is final.” “This is the order.”

These are not just summaries of what has been observed so far. They are assertions that rule out future observations.

Once such a claim is made public, the system is committed to it. Future events must be handled in a way that preserves the claim—even if those events have not yet been seen everywhere, or at all.

This is where replication becomes a problem.

One replica may expose a claim based on the information it has, while another replica is still in a position to observe something that contradicts it. An observer may learn the claim before the evidence needed to justify it has fully propagated. At that point, the system cannot simply “update” the observer’s view without violating the meaning of what it already said.

The same pattern we saw in the earlier lenses reappears here.

Waiting for arrival is easy because exposing evidence cannot be invalidated by later events. Waiting for non-arrival is hard because it exposes an absence that might still be contradicted.

Partial order is easy because exposing causal relationships can only be strengthened by more information. Total order is hard because exposing it rules out alternative explanations that might still be consistent with unseen events.

Seen this way, the core question is not about waiting or ordering at all. It is about which kinds of statements a system can safely expose before it has seen everything, and which ones require extra care.

Some statements are safe to reveal as soon as they are known locally. Others are only safe once the system has taken steps to ensure that no future observation will contradict them.

That difference is what brings coordination into the picture.

Conclusion: when you need a chisel

Throughout this post, we’ve been looking at how systems stay within spec—by ruling out behaviors they won’t allow. What the three lenses show is that there are two very different ways this happens.

When a system reacts to evidence, the space of possible executions shrinks as information accumulates. This is why replicas can diverge temporarily and still reconcile. They may see events in different orders, but as they exchange information, their views converge. Evidence removes ambiguity on its own, without anyone having to declare which futures are allowed.

The hard cases are different. Here, the system wants to rule out futures that the world has not ruled out yet. It wants to say that nothing else will happen, that a result is final, or that a particular ordering is settled and cannot be revised. Those futures are not impossible—they are merely unwanted.

At that point, the system can no longer rely on monotonic accumulation alone. The passage of events will not do the work for it. To stay within spec, the system has to actively forbid certain futures and get all participants to respect that decision.

That is what we usually call coordination.

Coordination is not about slowness or synchronization for its own sake. It is the extra machinery a system needs when correctness depends on excluding futures that might otherwise still occur.

This distinction shows up again and again: in transactions and isolation levels, in bulk-synchronous execution, and in systems that must act before all uncertainty is resolved. Those connections are worth exploring, but they’re for later posts.

For now, the takeaway is this. If the futures you want to rule out will be ruled out anyway by the arrival of information, staying within spec is easy. If they won’t be, the system will need help.